Turkey’s President Is Close to Getting What He’s Always Wanted

EghtesadOnline: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s statue in the main square of Rize, a small town nestled among tea plantations on Turkey’s Black Sea coast, has been gone since December. Its absence is a powerful symbol of the future.

Rize is the birthplace of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and his critics believe the question of what he really wants is finally clear after 15 years of his rule: To erase the secular state Ataturk rescued from the dismembered Ottoman Empire and recast the republic in his own, equally autocratic yet more Islamist image, Bloomberg reported.

Turkey is changing, said Nabi Avci, a long-time adviser to Erdogan and now minister of culture and tourism, but without any need to destroy Ataturk’s republic or the Turkish democracy that emerged since his death. Avci accused Erdogan’s opponents of forever crying wolf.

“A suit was made for Turkey to fit into at the beginning of the 20th century, but the world has changed a lot since then,” he said, citing the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the Arab Spring and other geopolitical shifts. “We are tailoring a new suit for Turkey.”

Never has answering the riddle of Erdogan’s true goals seemed more urgent. As early as this week he is expected to call an April referendum to approve constitutional changes that would concentrate all executive power in the presidency, abolish the post of prime minister, and give him greater control over judicial appointments.

Trump Era

At the same time, a wave of nativist populism sweeping Europe and the U.S. has loosened Turkey’s western anchor. The Turkish military, the second-largest in NATO, is fighting in Syria, and a once booming economy has stalled under the weight of terror attacks and the political clampdown that followed last year’s failed military coup.

Erdogan’s purging of the courts, crackdown on media and meddling in central bank policy have turned markets against him. The lira has lost a quarter of its value against the dollar since April. While his growing nationalism and populist style fit well into a world run by the likes of U.S. President Donald Trump and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, the new American administration’s anti-Muslim policies present risks for Turkey, too.

Using the same top-down methods as Turkey’s founder, Erdogan is remaking the republic as overtly religious and with its ambitions squarely in the former Ottoman lands of the Middle East, said Soner Cagaptay, author of “The New Sultan,” a soon-to-be-published biography of the Turkish president. “Erdogan,” he said, “is the anti-Ataturk ‘Ataturk’.”

Empty Pedestal

In Rize, almost 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) east of the cosmopolitan metropolis of Istanbul, some Turks hostile to the westernization Ataturk brought their country celebrated when an orange crane lifted his statue from its pedestal. It was moved to a lesser spot across town.

“Praise Be to God. Rize Has Been Liberated,” proclaimed a story on the website of the Islamist daily newspaper Akit. It later took the story down.

Secularists were outraged. Ataturk had been demoted to make way for a future monument to those who died defending Erdogan against July’s failed military coup. The square is now a construction site. They saw further evidence that Erdogan is replacing the secular, westward-looking state, complete with its own founding myth: his victory over the coup.

Then, last month, the Education Ministry published a new draft school curriculum that would reduce coursework on Ataturk, study jihad under the rubric of values, and remove a unit on theories of evolution, according to Impact-se, a non-profit that measures school systems against UNESCO standards. In a press release, it called the draft a “bellwether as to the intentions of President Erdogan.”

“The amazing thing is how easy it ultimately turned out to be to undo the republic,’’ said Soli Ozel, professor of international relations at Istanbul’s Kadir Has University. The rise of Trump and populists across Europe will help entrench Turkey’s own brand of nativism, he said.

Historical Depth

Now Erdogan needs to legitimize the powers he has assumed in a new constitution, according to biographer Cagaptay, who is Turkey program director at the Washington Institute, a U.S. think tank.

That’s because Erdogan is working with a literate, urbanized electorate on whose votes he depends, and half of which opposes him. By contrast, Ataturk imposed his radical reforms as a 1930s autocrat, a time when 80 percent of the population were farmers and only 10 percent could read, according to Cagaptay. With almost half the population resisting Erdogan’s changes, his centralization of power is a recipe for rolling crises and emigration, he said.

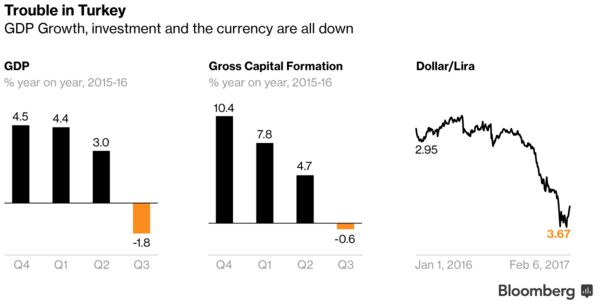

Erdogan and his Justice and Development party, or AKP, remain popular, in large part because they delivered efficient government and a rapid rise in wealth, with annual growth peaking just below 10 percent in 2010 and 2011. But the economy slowed sharply last year, shrinking in the third quarter.

Avci acknowledges that Erdogan has big plans to restore Turkey to greatness by the 100th anniversary of the Republic in 2023, a largely economic task. It is a status a country of Turkey’s size and “historical depth’’ was for too long denied, he said in his Ankara office, where the customary black-and-white portrait of Ataturk hangs over his desk.

Tailor Made

Opponents say Erdogan’s true Islamist instincts are emerging and fear these will shape the “New Turkey” he always talks about. Supporters insist Erdogan is simply allowing Turkey to reflect the values of its conservative majority, suppressed by the militant secularism of the old republic. The constitution will continue to enshrine Turkey’s secular state, with no mention of sharia law.

“He is collecting together the fabric, the needle, the scissors so he will now be able to become the tailor and can make the dress he wants,” said Gurcan Dagdas, a cabinet minister in 1990s and nationalist opponent of Erdogan.

Across the nation, in towns such as Rize, the government is renaming streets and squares after the victory over last year’s coup plotters, which Erdogan calls Turkey’s “second War of Independence.’’ The original was Ataturk’s 1919-1923 battle to expel Allied forces, end the Caliphate and carve out Turkey’s national borders.

Thousands of new mosques have been built, including inside the compound of Erdogan’s vast new presidential palace. The number of students attending religious Imam Hatip schools -- Erdogan went to one himself -- rose to just over than 1.1 million last year, from a low of 71,000 when AKP came to power in 2002, according to Turkey’s Education and Science Workers’ Union.

Chaos or Stability

Meanwhile, Turkish foreign policy is more focused on goals in the Middle East than at any time since the Ottomans. Negotiations to join the EU, which Erdogan started in 2004, are all but abandoned, with fault on both sides. Erdogan and top government officials accuse the U.S. and Europe of plotting against Turkey on an almost daily basis.

“We have broken feelings against our friends and allies,’’ said Avci. “So we will change Turkey.”

The new constitution would bring the law into line with powers that Erdogan has already assumed “indirectly,” and which he needs to be able to deal effectively with multiple threats, including terrorist attacks by Kurdish nationalists and Islamic State, which Avci calls by its Arabic name Da’esh. “We are making a choice between chaos and stability,” he said.

Any chaos is partly of Erdogan’s making, according to Ertugrul Gunay, a former member of Ataturk’s Republican People’s Party who then joined Erdogan to serve for five years as minister for culture and tourism. Gunay said Erdogan’s early effort to fit into Turkey’s secular political system and lodge Turkey in the EU was genuine, but that he has now driven himself and the nation into a dead end.

“Erdogan is a pragmatist and an opportunist,’’ rather than an Islamist ideologue, said Gunay. “He is defending himself. The problem is that we cannot make progress on any given path just based on one man protecting himself.’’

Muslim Brotherhood

It’s not all Erdogan’s fault, said Gunay, because the West changed too. After Erdogan enacted reforms necessary for EU membership negotiations to start in 2005, France, Germany and other governments promptly froze the process, aware of rising anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim feeling in their own countries. The big change, however, came with the 2011 Arab Spring.

Rejected by the West, Erdogan saw an opportunity for himself, then prime minister of the region’s most successful economy and democracy, to become “the leader of the new leaders’’ he hoped would emerge in former Ottoman territories from Egypt to Syria, said Gunay. Many of these new governments shared his own roots in the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots.

Increasingly frustrated in Syria, where he again backed Sunni Islamists, Erdogan was shaken a year later by what began as environmental protests in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, seeing them as an extension of the Arab Spring movement, only this time aimed at him, said Gunay. Erdogan cracked down hard.

Protests had erupted in Egypt at the same time, ending in a military coup that toppled President Mohamed Mursi, the Muslim Brotherhood candidate backed by Turkey. In response, Erdogan organized huge rallies at home to demonstrate his ability to bring people into the streets, should the military try the same in Turkey -- as it did last year.

Now estranged from Erdogan, Gunay sees his latest actions and new constitution as threats to Turkey’s democracy. He likened his former boss to Enver Pasha, one of the triumvirate of military officers who seized power in Istanbul in 1913. Enver’s unrealistic ambitions to restore the empire to greatness led him to side with Germany in World War I, instead accelerating its collapse.

“So many compare him now to Ataturk, some to please him and some to criticize him,” he said. “But Erdogan is no Ataturk.’’