'Apocalyptic' Flooding Has Harvey's Damages Rising by the Hour

EghtesadOnline: On Tuesday morning, disaster analyst Chuck Watson had pegged $42 billion as a reasonable estimate for the cost of destruction Tropical Storm Harvey would leave in its wake. By the end of the day, he’d added another $10 billion.

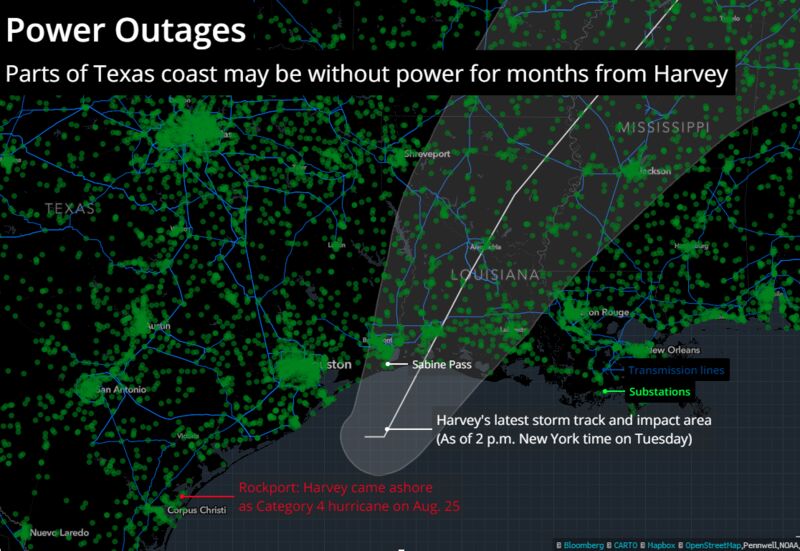

Harvey’s initial blast along the Texas coast as a Category 4 hurricane was bad enough, sending gasoline prices surging and crude futures plunging as refineries shut. Then came the torrential rains and the collapse of levees, dams and drains. That combination has analysts raising damage estimates by the hour and could easily push the catastrophe above the rank of Superstorm Sandy, the second costliest weather disaster in U.S. history, Bloomberg reported.

“We’re on the verge of having cascading failures,” said Watson, a Savannah, Georgia-based disaster modeler with Enki Research. “It is conceivable that we could get into the $60 to $80 billion range without that much effort.”

What’s more, Harvey is threatening Louisiana, including New Orleans, which was devastated by Katrina in 2005. That hurricane killed at least 1,800 and caused $160 billion in damage. Sandy, which slammed into New York and New Jersey in 2012, claimed 147 lives along its path from the Caribbean, including 72 in the U.S. The damage was about $70.2 billion, according to the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information in Asheville, North Carolina.

The death toll from Harvey had reached at least 15 on Tuesday, according to the Austin American-Statesman newspaper. It made landfall between Port Aransas and Port O’Connor in Texas on Friday, stalled out further inland over the weekend and is now trekking eastward along the edges of the Gulf Coast.

“Harvey aligned perfectly to bring intense rain bands over Houston,” said James Done, a project scientist and meteorologist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. As it drifted along the coast Monday and Tuesday, it also “perfectly aligned for Houston to get the peak rainfall.”

Harvey also created a situation where Gulf of Mexico waters have kept drumming hard up against the coastline, preventing rain water from running off into the sea and backing everything up for miles around.

The ferocious arrival was tempered by high-pressure systems across the U.S., including a large one that pushed temperatures in California beyond 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 Celsius), said Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University. Harvey became “a pebble in stagnant stream.”

Predictions were that some areas east of Houston would witness 50 inches or more of rain by the time Harvey moved off into the central U.S. As of 3:29 p.m. local time Tuesday, the gauge at Mont Belvieu, east of the city, showed 51.88 inches had fallen since the start of the storm. That may be the most in recorded history for a tropical cyclone in the contiguous U.S., breaking a mark also set in Texas back in 1978.

The record for all 50 states in such a storm was set in 1950 in Hawaii -- 52 inches.

Harvey’s deluge was made all the worse because the ground was already saturated by heavy rainfall earlier in the season. “We have had roughly a year’s worth of rain in the last three months,” said Wendy Wong, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Dickinson, Texas, a city that was evacuated.

Watson said disaster models just aren’t calibrated for a thing like Harvey. For instance, a typical scenario will assume infrastructure like dams, levees and drainage system will fail when stress rates reach 80 to 90 percent. “We are seeing failures at 60 percent,” he said.

The pressure on the Addicks and Barker reservoirs west of Houston spurred the Army Corps of Engineers to release water, which flooded neighborhoods that had been dry before. Now such deliberate flooding should be more calculated, Watson said.

“We’re starting to get into the apocalyptic -- this is what we don’t want to have happen.”

The Army Corps didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment, but said earlier on Tuesday that no decision had been made to increase discharge rates and that dam releases were expected to occur for several months.

Watson’s other concern is how slowly water is draining away from Houston. Done said the reason may be that Harvey’s surge is keeping up pressure on bays, inlets and the mouths of rivers, preventing runoff.

It could also be evidence that the pipes and drainage systems are failing, Watson said. That, of course, would increase the ultimate financial pain of the storm.

‘Precarious Situation’

Now, New Orleans and the rest of coastal Louisiana are feeling the brunt of Harvey’s soaking rains, threatening yet another major U.S. refining center. The hurricane center said 5 to 10 inches could fall across eastern Louisiana, including New Orleans. Mississippi, Arkansas and Alabama could soon get as much as 8 inches.

The infrastructure in New Orleans, “can barely keep up,” Done said. “New Orleans is in a very precarious situation.”

The forecast calls for the storm to continue into the central U.S., arriving over Kentucky as a tropical depression Saturday. And even then, Houston won’t be free from threats.

Rainfall over the state will eventually need to make its way into the Gulf, which means several more pulses of water could be coming the city’s way, Watson said.

“There is another train that is heading toward Houston,” Watson said. “Behind every one of these dollar signs is a family that doesn’t have a house anymore.”