China Is Taking On the ‘Original Sin’ of Its Mountain of Debt

EghtesadOnline: China’s much-vaunted campaign to tackle its leverage problem has captured headlines this year. But to understand why they’re taking on the challenge -- and the threat it could pose to the world’s second-largest economy -- you need to dig into the mountain.

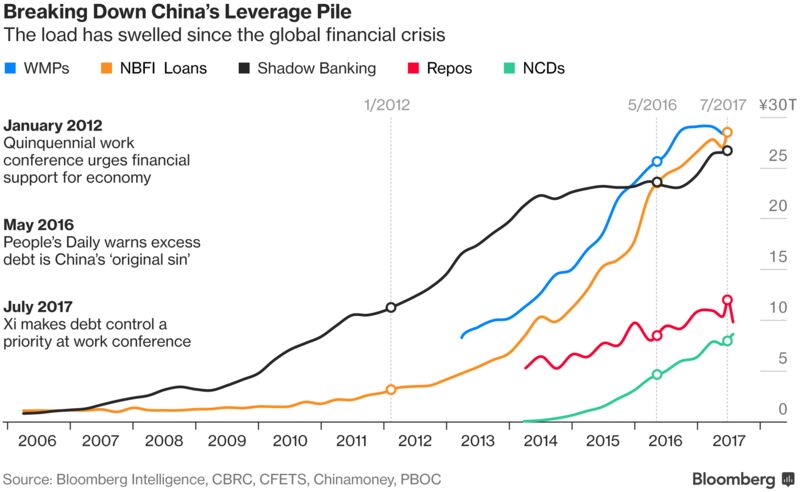

Characterized in state media as the “original sin” of China’s financial system, leverage has swelled over the past decade -- partly because policy makers were trying to cushion a slowdown in growth from the old normal of 10 percent plus. What’s fueled the leverage has been a rapid expansion in household and corporate wealth looking for higher returns in a system where bank interest rates have been held down, Bloomberg reported.

The unprecedented stimulus unleashed since 2008 effectively brought to life the “monster” China’s leadership is now trying to tackle, says Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research Ltd. in Hong Kong and author of “Shadow Banking and the Rise of Capitalism in China.”

Implicit backing from the central government meant borrowers had free license to take on debt.

“You basically have anybody selling anything they want as they think they can’t lose,” Collier said. Deleveraging -- championed by President Xi Jinping and the Communist Party Politburo in April -- hasn’t truly begun, as “they’re trying to forestall the pain as long as possible,” he said.

The equivalent of trillions of dollars are now held in all manner of assets in China, from high-yielding wealth management products to so-called entrusted investments.

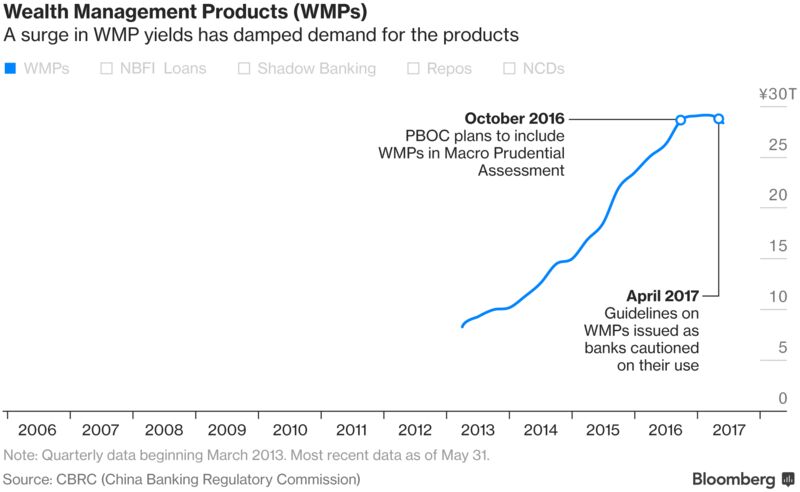

Taking the heftiest piece of the leverage mountain first, wealth management products had a precipitous rise over the past several years.

A way for borrowers who have trouble getting traditional bank loans to win funding, WMPs have grown in popularity as they typically offer savers much higher yields than banks offer on deposits.

WMPs are also a hit because they give lenders a way to keep loans off of their balance sheets, and to skirt regulatory requirements when channeling funds to borrowers, according to Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. in Hong Kong.

The regulatory crackdown this year -- mostly in the form of more stringent guidelines on use of financial products -- has seen the amount of WMPs outstanding taper off from a peak in April, while yields on them have surged as providers competed for funds. In July, the bank watchdog is said to have told some lenders to cut the rates they offeredon the products.

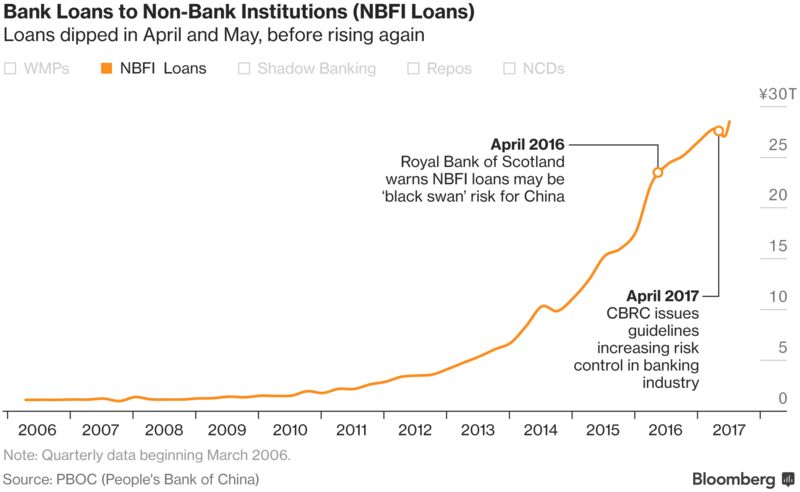

Turning to loans by banks to non-financial institutions, this is an area that’s yet to be dented much by what Xi has characterized as a de-risking drive. Yeung says the leadership’s campaign poses a “real test” for China and its regulators.

“On the one hand, they don’t want this overall deleveraging to have any negative impact on real economic activities,” he said. “At the same time, they know if they don’t do it right now that it will become another financial bubble pretty soon.”

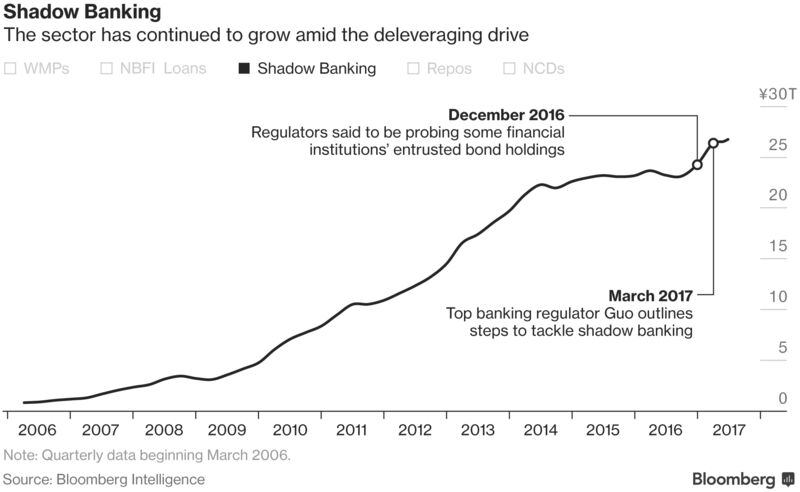

Since regulators ramped up their measures to curb financial leverage at the start of April, shadow banking has been in the cross-hairs.

The most popular forms include entrusted loan agreements (when a company lends money to another company with the bank as the middleman), trust loans (where banks use money raised from WMPs to invest in trust plans, with the proceeds eventually going to a corporate borrower) and bankers’ acceptances (a bank-backed guarantee for a future payment).

Data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence tracking all three sectors show shadow banking still amounted to a record 26.7 trillion yuan as of the end of June.

Shadow financing is seen as one of the culprits behind China’s property-price surge, and regulators this year banned private-equity lending to developers for land purchases. Banks also were told in March to submit reports on their entrusted investments -- funds that Chinese lenders farm out to external asset managers -- and Beijing recently extended the deadline after some struggled to determine the scope of their exposures.

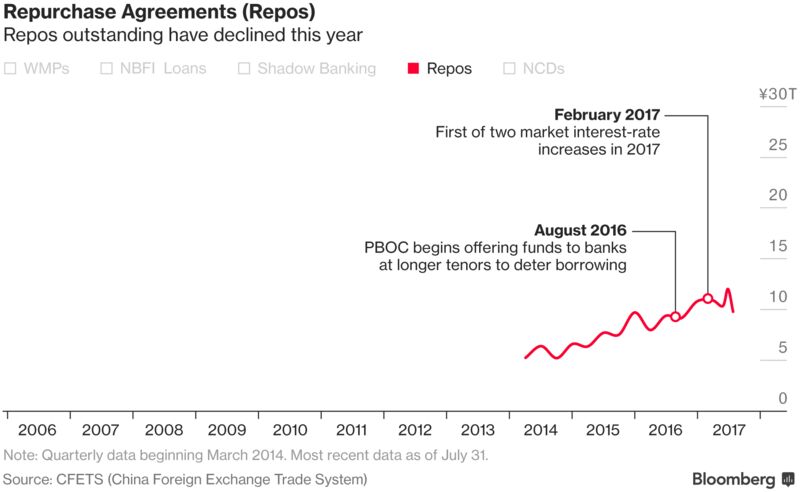

More directly connected to markets are repurchase agreements, where participants can get cash for set periods. A key tool for officials to rein in borrowing has been boosting funding costs in the money market. And indeed, the amount of repos outstanding has come off since reaching a peak at the end of June.

The People’s Bank of China in March hiked rates on reverse-repurchase agreements and also raised the cost of medium-term loans. HSBC Holdings Plc analysts are among those seeing some further boost to money-market rates.

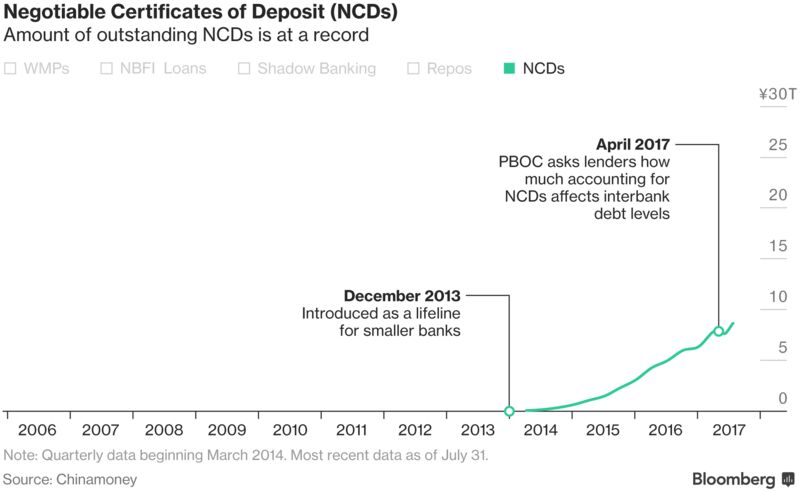

Negotiable certificates of deposit are relative minnows in China’s ocean of leverage, but they are a lifeline for smaller banks that have difficulty competing for savings against the big state lenders.

NCDs morphed into a way for small banks to fund purchases of each other’s WMPs, with a circular arrangement developing whereby the banks selling the products would then channel the proceeds into the bond market, resulting in a mismatch between the shorter-term NCDs and other debt investments.

After dipping slightly in May as the deleveraging rhetoric intensified, the amount of NCDs outstanding has started rising again, reaching a record last month.

Earlier in the year, the PBOC was said to be mulling requiring lenders to re-classify NCDs as interbank liabilities, a move that would likely quell their growth because of limits on how much interbank debt banks are allowed to hold relative to their overall liabilities.

China’s monetary authorities for years focused on incubating innovation in the financial system, after decades when Soviet-style command and control was the model. Having successfully overseen an explosion in new types of credit, they are having to pivot into the role of gatekeepers and supervisors -- and to coordinate themselves better as risks pile up, according to Yeung and his colleagues at ANZ.

“This will certainly challenge the technical abilities as well as the mindset of regulators.”