The Sunny Side of Trump

EghtesadOnline: The second-biggest surprise of November, after the election of Donald Trump, has been the warm reception the president-elect has gotten from businesses and investors. Before Nov. 8 the consensus was that a Trump victory would tank the stock market. Instead, stocks have risen.

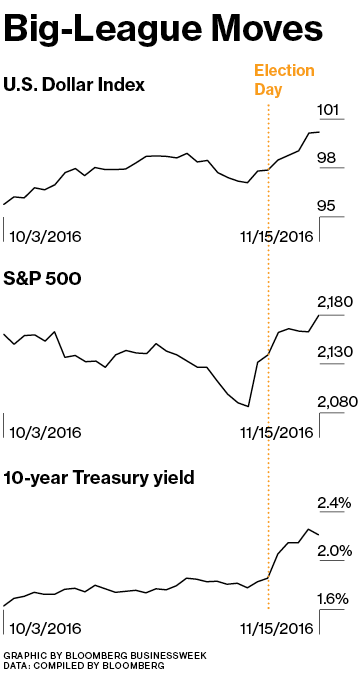

According to Bloomberg, the dollar is up. Several economists have raised their projections for economic growth in 2017 and 2018. On Nov. 15 one of the most heeded figures in the investing world tiptoed up to the edge of saying something nice about the makeup of the embryonic Trump administration. “There’s a good chance that the ‘craziness’ factor will be smaller and play a lesser role in driving outcomes than many had feared,” Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s biggest hedge fund, wrote on LinkedIn. “Our very preliminary assessment is that on the economic front, the developments are broadly positive—the straws in the wind suggest that many of the people under consideration … probably won’t recklessly and stupidly drive the economy into a ditch.”

Even some of Trump’s fiercest opponents are backing down from the equation that Trump equals calamity. In a Nov. 14 New York Times op-ed, Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate economist, wrote that while he continues to believe electing Trump was a grave error, “don’t be surprised if economic growth actually accelerates for a couple of years.” Businesspeople who are weary of Washington gridlock are optimistic something might actually get done. This is the first time since Dwight Eisenhower was elected in 1952 that a Republican president will enter office with GOP majorities in both the House and the Senate. “It has been roses and sunshine,” Tom Cole, a Republican representative from Oklahoma, told reporters.

How long will this honeymoon last? For American business, the positive scenario is that Trump appoints sensible people, matures in office, and puts most of his considerable energy into the pro-growth parts of his agenda. The negative scenario is that he goes back to being the inciter who flew off the Twitter handle so much during the campaign that his people temporarily seized control of his account.

For now people are accentuating the positive, as this essay and several other stories in this issue reflect. Trump was presidentially gracious in his victory speech. He’s continued to talk up tax cuts, infrastructure spending, and deregulation. He named Reince Priebus—a conciliatory, conventional Republican—to be his chief of staff. He didn’t stand in the way of Paul Ryan’s reelection as speaker of the House. There was talk that he could name former Goldman Sachs partner Steven Mnuchin, who was his finance chairman, to be secretary of the Treasury. Part of that famous wall on the Mexican border will be a simple fence now, and the once-promised deportation force to expel undocumented aliens is gone from his rhetoric.

Being positive about Trump means believing he won’t do many of the things he’s promised

Stocks of financial companies in the S&P 500 jumped about 11 percent in the week after the election, presumably because investors believe Trump will dismantle the Dodd-Frank Act. Industrials rose almost 6 percent on hopes for infrastructure spending. The prospect of lower taxes on corporate profits is also good for stock prices.

The market’s positive reaction might help steer Trump toward market-friendly measures. During the campaign, he basked in the adulation of his fans and emphasized the promises that drew the biggest applause and the most retweets, such as locking up Hillary Clinton. To Trump, the rise in the S&P 500 probably looks a lot like a standing ovation from Wall Street. If he’s true to form, he’ll want more applause from the stock market, which could lead him to adopt policies that are friendly to business.

Despite being a billionaire, Trump never got much love from the business establishment. Through mid-October, just one chief executive officer of an S&P 100 company—David Farr of Emerson Electric—had donated to him. Eight gave to Clinton, including Apple’s Tim Cook, Verizon Communications’ Lowell McAdam, and Coca-Cola’s Muhtar Kent. But now that the election results are in, businesses are trying to accommodate to the new reality in Washington. There’s no percentage for a CEO in standing up against a president he or she doesn’t like. Transcripts of analyst calls compiled in Bloomberg’s Orange Book reveal the tone. Walt Disney CEO Robert Iger volunteered on Nov. 10 that the company has already prepared a bust of Trump to go into Disney World’s hall of presidents. Union Pacific Chief Financial Officer Robert Knight Jr. told analysts on Nov. 9, “I guess broadly said, I’m not pessimistic about where this is going to go,” even though UP is vulnerable to a trade war with Mexico because of its cross-border rail traffic.

Business lobbyists, nothing if not politically agile, are soft-pedaling their differences with Trump over trade and immigration. They’d rather work out those disagreements in smoke-free back rooms than in the press. “What’s most important for the chamber and our members is that our country unites around a mission to have a stronger economy, not just for business but for our workers and the people of our country,” Myron Brilliant, executive vice president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, said in an interview the day after the election.

The bullish case for a Trump presidency is that corporate tax cuts will unleash investment in equipment, buildings, and software. Joseph LaVorgna, Deutsche Bank’s chief U.S. economist, predicted on Nov. 15 that the economy’s annual growth rate will accelerate from 2 percent in the first quarter to 2.5 percent in the second, to 3.5 percent in the third, and to 4 percent in the fourth, before ramping down gradually in 2018. “Last week’s election results were a seminal event and could have profound economic implications,” LaVorgna wrote. “Massive fiscal expansion could go a long way to restoring a much faster pace of economic activity.”

It’s also quite possible that the Trump presidency will be an economic failure. The dirty secret of macroeconomics is that it’s actually easy for a sitting president to goose the gross domestic product higher for a year; increases in spending and cuts in taxes reliably do that, as Krugman conceded in his op-ed. The problem, which fiscal conservatives never tire of pointing out, is that a zap to GDP that’s achieved through deficit spending will have to be paid back with higher taxes that sap growth in the future. According to the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Trump’s plan, if enacted as written, would cause federal debt held by the public to swell to 105 percent of GDP in 10 years, up from 77 percent now. “The first principle is not to be fooled by increases in measured gross domestic product,” George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen wrote in a column for Bloomberg View.

A higher tariff on imported goods is, of course, nothing more than a new tax

Congressional Republicans resisted Keynesian economic stimulus when the unemployment rate was high and the economy could have used it more. Now that a Republican is entering the White House, markets are betting that the fiscal conservatives will set aside their principles and give Trump a victory. The spike in yields on Treasury bonds indicates market expectations of higher inflation resulting from stronger economic growth. But the economy could fall back into torpor if businesses and consumers lose faith that the spurt is sustainable.

Trump’s expansion could end up benefiting the elites more than the masses. The Wall Street rally is enriching the stockholding upper-middle class, while the runup in interest rates is penalizing the people who need to borrow to buy the car that gets them to work. Meanwhile, the president who inveighed against trade deficits could actually cause them to expand by revving growth. “The boost to domestic demand from the fiscal stimulus will draw in more imports, counteracting the desired goal of shrinking the trade deficit,” write Macroeconomic Advisers economists Chris Varvares and Joel Prakken. Likewise, a tit-for-tat tariff war with Mexico or China would whack the poor and working class more than the rich because more of their income goes for goods, vs. services such as ballet tickets or tummy tucks. A higher tariff on imported goods is, of course, nothing more than a new tax.

Trump won the election by making promises to his core constituents that were even more extravagant than the average candidate’s. He pledged to rebuild the military, protect Social Security and Medicare, and pay down the national debt, all while cutting taxes dramatically. Fulfilling any one of those four promises is possible, but doing all four at once defies logic. On the stump, Trump said he would at least double the economy’s 2 percent annual GDP growth rate and even talked about reaching 5 percent or 6 percent. But labor force growth is dwindling as boomers retire, and productivity growth depends on business investment and technological advances, which have been chronically weak. While growth-friendly tax policy could help, there’s no button in the Oval Office that says, “Press here for a stronger economy.” All of this is not what Trump’s supporters are prepared to hear right now: Gallup reported that the percentage of Republican voters who think the economy is getting better tripled, to 49 percent, from right before the election to right after.

The collision of hope and reality is likely to happen as soon as March, just two months after Trump’s inauguration, when the suspension of the ceiling on the federal debt ends. Republicans in Congress who used the debt ceiling as a weapon against President Obama are unlikely to roll over for Trump, especially because many aren’t convinced he’s one of them. “Republicans control Washington, but the meaning of the term ‘Republican’ has never been less clear,” Nuveen Asset Management senior portfolio manager Robert Doll wrote in a note to clients.

One of the first budgetary casualties could be Trump’s promise—a hit with business—to unleash $1 trillion in private infrastructure spending over the next 10 years. His economic advisers claim the spending wouldn’t raise the budget deficit because the only cost would be government inducements, in the form of credits against investors’ federal tax bills. The hope is that the loss on the credits would be offset by new taxes on the wages and profits of contractors. But the innovative formula might not pencil out with skeptical budget analysts.

The mixed signals from Trump’s transition team are also unnerving to business. Politically, Trump can’t fill his cabinet and inner circle entirely with boardroom types—his supporters would feel betrayed. He offset the appointment of Priebus as chief of staff by naming Steve Bannon to be his senior counselor and chief West Wing strategist. “Crony capitalism has gotten out of control,” Bannon told Bloomberg Businessweek after the election. “Trump saw this. The American people saw this. And they have risen up to smash it.”

One difficulty for business executives is that to be optimistic about a Trump presidency requires believing he won’t do many of the things he said he would do. If his positive agenda doesn’t produce results, he may be tempted to go negative, expelling millions of illegal immigrants or threatening trade wars with Mexico and China. Tech stocks have fallen slightly even as the overall market is up, a move that analysts attributed to fears of a trade war that would cripple supply chains and crimp sales.

While plenty of analysts have asked whether Trump might cause a financial crisis, fewer have pondered how he will react to a financial crisis that isn’t his fault. Henry Kaufman, the former head of research at Salomon Brothers, says deregulation-minded Trump could find himself fighting a fire that begins with the failure of a bank that’s too big to fail. Kaufman, 89, known as Dr. Doom, began his Wall Street career in 1949. “We’re much more at the financial edge than we were then,” he says. Already, the jump in U.S. interest rates and the rise of the dollar are putting pressure on emerging-market economies where people borrow in dollars, says Quentin Fitzsimmons, a global fixed-income portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price. That could be the start of an international crisis that would entangle the White House. “It’s plausible to argue that the risks to the rest of the world are higher than to the U.S. economy itself,” Fitzsimmons says.

The truth is that no one yet knows what Trump will do as president, not even Trump. After the election, Goldman Sachs’s index of U.S. economic policy uncertainty spiked to its highest level since it began in 1985. The enmity toward elites that Trump stirred up during the campaign may be stronger and more enduring than even he realizes, and it could impede his ability to get things done. “The rise of populism, the impact on sentiment, will continue far beyond the November election,” Henry McVey, head of global macro and asset allocation at private equity giant KKR, predicted before the election.

For people who have turned optimistic on Trump, it’s a case of “shoot first, ask questions later,” says Steven Ricchiuto, chief economist at Mizuho Securities USA. “This is the first growth story they’ve had in eight and a half years, and they’re going to run with it.”

Trump backer Peter Thiel, the billionaire venture capitalist, popularized an observation by writer Salena Zito of the Atlantic, which is that the press takes Trump literally but not seriously, while his supporters take him seriously but not literally. For business executives, taking him seriously but not literally amounts to believing in the parts of his message that make sense to them and discounting the parts that they think are beyond the pale.