Spain’s Mom and Pops Are Hurting

EghtesadOnline: Spain’s robust economic recovery hasn’t buoyed Ricardo Sainz’s half-century-old grocery store in Madrid’s working-class neighborhood of Orcasitas. Sales have fallen from roughly €25,000 a month ($27,000) before the recession began in 2008 to €10,000 today. And he expects them to keep slipping.

His faithful older clients are dying, and younger generations prefer the nearby chain supermarket. All his employees have left, and he isn’t replacing them. The shopkeeper works by himself, 11 hours a day, six days a week. “The recovery is helping some,” he says. “But not businesses of my size. The system doesn’t support us.”

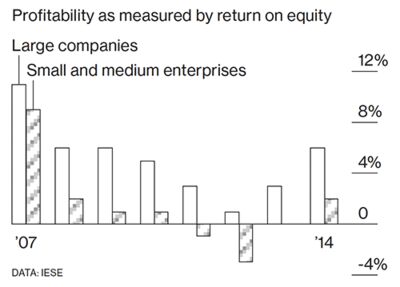

According to Bloomberg, revenue at small and midsize companies in Spain dropped 32 percent from 2007 to 2014, and their head count was down 27 percent on average, according to an IESE Business School study of 1.2 million businesses of various sizes published in November. Sales were steady at their larger counterparts, which increased their workforces by 7 percent.

Like Sainz’s shop, almost 96 percent of Spain’s 3.2 million businesses are tiny, with no more than nine employees and less than €2 million in annual revenue. These microbusinesses, as they’re known in Spain, account for 33.5 percent of private-sector employment, more than 4 percentage points higher than the European Union average.

A BBVA Foundation analysis from last year noted that Spain’s microbusinesses don’t generate much revenue or last very long, which makes them a drag on productivity. “In most cases, they don’t have the will or the way to transform themselves into small or midsize businesses,” says Rafael Doménech, chief economist for developed economies at BBVA Research. “The question is, how do we get them to keep climbing the ladder of growth? It’s one of the biggest structural challenges the Spanish economy is facing.”

Still smarting from the collapse of his 40-employee office-furniture business in 2014, Juan Carlos Giménez doesn’t aspire to climb the ladder again. He sold his home and drained his savings as his 26-year-old company descended into bankruptcy. Giménez, his wife, and a few colleagues started a consulting company in 2015, so they could make use of their industry expertise to help other furniture makers without having to hire employees or taking on other major fixed costs. It will generate a sliver of the €11 million in annual revenue his former business brought in before the downturn.

Since the crisis began, the government has passed an assortment of laws meant to spark confidence, including measures making it easier for entrepreneurs to hire and fire employees and access credit. They’ve helped, but the approach has been “very piecemeal,” says Gayle Allard, an economist at IE Business School in Madrid. “Entrepreneurs came out of the crisis scared,” says Giménez. “Even though they know people are the most important part of any business, they don’t want to invest in them or take on other risks.”

Financing costs in Spain are the highest among major European countries—and small companies pay significantly more interest than their larger counterparts, according to a December report by the Spanish business group CEPYME. A more significant hurdle is getting clients to pay on time, says Antonio Garamendi, CEPYME’s chairman, who estimates that it takes three months on average to settle an account. “This is the problem that chokes small and midsize businesses,” he says. “Instead of concentrating on the future of the business, the owner gets distracted figuring out how to make payroll due tomorrow.”

Madrid-based entrepreneur Javier Goyeneche, who steered his handbag business through bankruptcy before selling it during the crisis, has been underwhelmed by government policies. “If entrepreneurs had received more help, the recovery would be much quicker,” he says. He started a new company, Ecoalf, in 2012 that sells clothing and fashion accessories made of recycled materials. He expects the 30-person operation to come close to breaking even this year. “What’s needed are thousands of companies like this,” he says. “It’s not just about creating businesses. The other part is expanding them. Because if not, they get stuck at a size that makes it difficult for them to survive.”

The bottom line: About 34 percent of Spain’s private-sector jobs are at very small companies, many of which are still hurting from the recession.