In Putin’s Parliament, Plunging Popularity Is No Hurdle to Power

EghtesadOnline: Ruling parties hoping to get re-elected during a prolonged recession usually pitch fresh ideas for easing the population’s economic pain.

But that’s not how Vladimir Putin’s party operates.

Thirteen years after gaining control of parliament and five years after last retaining it, United Russia’s platform for this weekend’s contest is little more than a vow of continued subservience to its creator, the country’s president, according to Bloomberg.

“We pledge, together with all of you, to work for the country’s benefit” is one typical extract from the manifesto, which mentions neither Russia’s largest decline in wages in two decades nor the millions of people who’ve fallen into poverty since the last parliamentary ballot in 2011.

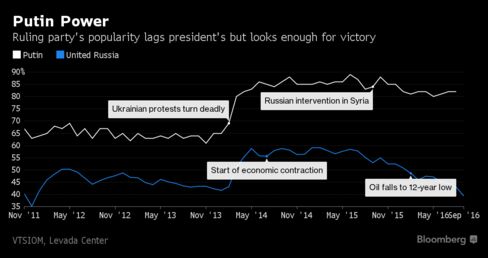

The lack of inspiration is reflected in polls showing United Russia’s support tumbling to about 40 percent from 60 percent in just 18 months, which would be the its worst result since its first contest in 2003. Even so, Putin values stability above all and that’s just what his system will deliver on Sept. 18, when new election rules will ensure the party retains or even expands its majority, former Kremlin officials and party leaders say. For this vote, Putin reinstated single-mandate districts, which benefit the party in power since it’s backed by the state machinery and remains more popular than its rivals.

“The result will be considered a good one,” said Konstantin Kostin, who ran the presidential administration’s internal politics department during the last election and now heads a think tank. “Putin is a conservative,” so there won’t be any sudden economic reforms because “that would carry risks,” he said.

Putin, who faces his own election battle in March 2018, is seeking to avoid the eye-witness reports of ballot-stuffing and other forms of ballot-rigging in 2011 that sparked the biggest protests since he came to power 17 years ago.

In March, Putin chose a veteran human-rights advocate, Ella Pamfilova, to oversee elections and promote clean campaigns. Then he toughened restrictions for vote monitors and created a paramilitary force of 340,000 troops whose tasks include suppressing mass demonstrations. Last week, authorities declared the country’s only independent polling company, Levada Center, a “foreign agent,” a designation that may drive it out of business.

While the Kremlin has made deft use of its media monopoly to rally support for the wars in Syria and Ukraine and keep Putin’s approval rating above 80 percent, a third of the public says the country is headed in the wrong direction. More people are blaming lawmakers, not the president, for spending cuts introduced after oil prices plunged, surveys show.

Pension Hit

Backing for United Russia fell sharply in August after parliament decided to replace pension increases tied to inflation this year with a one-time payment of 5,000 rubles ($78), according to Alexei Grazhdankin, deputy head of Levada.

Yet the party, founded to buffer Putin after he came to power in 2000, offers virtually no concrete economic pledges other than to seek a balanced budget and slower inflation. The other three parties in parliament all have proposals that cater to average workers.

The Communists, polling at about 10 percent, want to restore free medical care and education for all and introduce “tough” measures to combat corruption. Nationalist firebrand Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s LDPR seeks a minimum wage of 20,000 rubles a month. Fair Russia opposes raising the retirement age and advocates minimum pay of 100 rubles an hour.

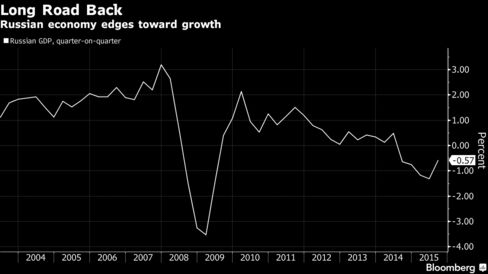

The next parliament, and then likely Putin himself, will start their new terms in a period of economic and geopolitical uncertainty unlike any other in post-Soviet Russia, according to Chris Weafer, a partner at Macro Advisory in Moscow. Cuts in public spending and “stagnant” medium-term growth of about 1.5 percent are new challenges for Putin, who oversaw a near-doubling of the economy during oil’s historic rally in the 2000s, he said.

“Putin needs to deliver on growth expectations before long,” Weafer said. “People want jobs, they want income growth, they want the better lifestyle that they’ve been promised and have already had a taste of.”

In an interview this month, Putin brushed off United Russia’s dip in the polls as a natural byproduct of a healthy political contest, when criticism of the leading party peaks.

“What happened?” he asked rhetorically in Vladivostok. “Nothing happened. It is just that an active election campaign has started.”

His confidence may be partly the result of the new electoral rules. Half of the Duma’s 450 seats will be decided in individual contests, with the rest split between parties that get more than 5 percent of the vote nationwide. In 2003, when Russia last had single-member district races, United Russia gained a two-thirds majority with less than 38 percent of the vote. Its support peaked at 64 percent in 2007 and slid to less than 50 percent in 2011.

Avoiding ‘Tragedy’

It would’ve been a “tragedy” for Putin if his party had to fight for seats based only on the nationwide results, “so the Kremlin took out an insurance policy,” said Alexei Mukhin, head of the Center for Political Information in Moscow.

A senior United Russia official, Vyacheslav Nikonov, said he expects his party to get “significantly more seats” than the 238 it holds now because of the“clear advantage” it enjoys in the stand-alone races.

Beyond the loyal opposition, the liberal Yabloko party and the new pro-business Growth party may pick up a few seats, according to Valery Fyodorov, who runs state pollster VTsIOM. There isn’t much chance for Parnas, a party backed by one of the leaders of the 2011 protests, Alexei Navalny, he said.

For now, as long as Putin supports United Russia, there’s nothing on the horizon that would suggest the party is at risk of losing power, according to New York-based political risk consultancy Eurasia Group.

“The elections will demonstrate that even in a context of economic hardship, falling living standards and grim prospects for growth, the state is still quite capable of shaping both the narrative and the conduct of elections to its advantage,” Eurasia Group said in a research note.