Two weeks ago, Prime Minister Binali Yildirim joined the push, telling lenders, “You either do this on your own or we make you do it.’’

According to Bloomberg, the message now seems to have gotten through. Monday, two of the country’s biggest banks announced they were cutting lending rates. The next day, Yildirim summoned top executives from the industry for a meeting to discuss what more they could do.

At the session, the bankers said they “recognize their responsibilities to contribute more to speed up growth,” the prime minister’s office said in a statement. More banks joined the cuts.

Economy Slowing

Erdogan’s tough approach has helped him crush political rivals. Since putting down a coup attempt in July, security services have detained tens of thousands of suspected opponents in the military, government and academia. But the waves of purges, including a new one this week that brought arrests at a prominent opposition newspaper, have shaken an economy that was already slowing before the failed putsch.

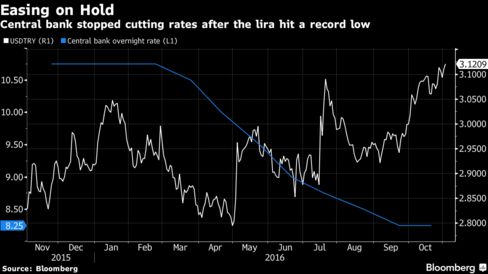

His efforts to use the same kind of tactics to get growth back in high gear haven’t been as successful. After pushing the central bank to cut rates for months earlier this year, it abruptly suspended the easing last month after the currency fell to a record low. Inflation remains stubbornly above targets and the continuing political upheaval has alarmed investors, both domestic and foreign.

“You can push interest rates lower, but you cannot force economic actors to take on more debt,” said Inan Demir, an emerging-markets economist at Nomura Plc in London. “Companies may be reluctant to take on more debt, even if at lower rates, if they are intimidated by the uncertainties,” he added, while “households are already leveraged and unwilling or unable to borrow more.”

Tourism, long a pillar of the economy, has collapsed in the last year as terror attacks and tensions with Russia have kept would-be holiday-makers away. Investment has stalled. Last month, the central bank warned that the economy continued to slow in the third quarter. The government reduced its growth forecast for this year to 3.2 percent, the lowest since 2014. Moody’s Investors Service in September cut Turkey’s debt rating to junk status, saying, “External vulnerability has risen” and noting “unpredictable political developments and volatile investor perception.”

Erdogan’s crackdown since the failed coup has extended far beyond the military officers directly involved, with more than 100,000 alleged followers of U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, who Erdogan has blamed for the coup attempt, ousted from their jobs and in many cases detained. Erdogan has imposed a state of emergency granting the government additional powers. Last week’s moves included an expansion of that authority, as well as a pledge to return the death penalty for traitors.

Widening Crackdown

“Roughly 200,000 people have been somewhat touched by the Gulenist investigations, creating deep-seated job insecurity, possibly lowering the propensity to consume,” said Atilla Yesilada, an economist at GlobalSource Partners in Istanbul. Financial markets remain nervous, with the main stock index down 6.8 percent since the abortive putsch.

This week, the central bank eased rules for banks’ holdings of foreign currency in an effort to head off a shortage that had pushed deposit rates higher.

“If there was strong growth, good wage growth, good employment growth and no credit growth, then you could argue, OK, maybe interest rates are the problem and the banks are the problem,” Michael Harris, the head of research at Renaissance Capital in London, said. “This is a demand problem - if there was a lot of good quality demand for credit, a nudge from the state banks could easily get the sector to price lending more aggressively."

Erdogan first began to lean on the banks to lend more in the weeks following the failed coup. “There’s a disagreement between me and bankers on rates,” Erdogan said early August.

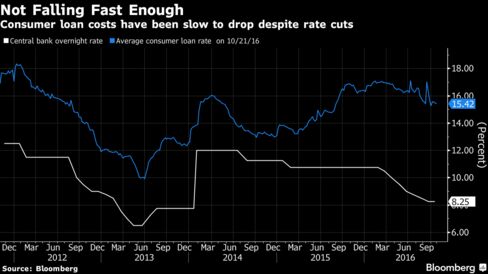

Within days, major banks had cut their home-loan rates, but the impact was limited. Mortgage lending has only recently begun to pick up. The gap between the rates banks charge on loans and what the pay on deposits remained high, suggesting there was more room to ease credit, according to Sadrettin Bagci, a banking analyst at Deniz Yatirim in Istanbul.

Slack Demand

By last month, the best the central bank could say was that loan growth stopped falling in the third quarter, with consumer borrowing picking up in the last few weeks. But the overall rate is still under 10 percent a year. For a country that’s depended on borrowing to fuel years of fast growth, that amounts to a painful slowdown. At the peak of the boom in 2011, lending grew at an annual pace of about 40 percent.

Banks said it wasn’t their fault. “We had weak borrowing demand from companies despite a strong appetite to lend by the banks,” said Huseyin Aydin, head of the Turkish Banks Association.

But the government wasn’t convinced. Late last month, the prime minister weighed in. In a speech, he accused banks of “loansharking,’’ calling on them to do more to support the economy.

It took little more than a week for the banks to announce more cuts.

“We talked about ways to revive the economy,” Ali Fuat Erbil, chief executive of Turkiye Garanti Bankasi AS, the country’s biggest bank by market capitalization, said after the meeting with the prime minister Tuesday. “I think the discussions were very positive for all the participants.”