Dudley’s contribution has been, in a nutshell, to get policy makers more focused on swings in the stock market and how they affect the economy. Inspired by the Bank of Canada in the mid-1990s, he’s been developing an idea ever since that could encourage the Fed to speed up -- or slow down -- the pace of interest-rate increases, depending on market movements, according to Bloomberg.

"I don’t think we are removing the punch bowl, yet. We’re just adding a bit more fruit juice," Dudley said Thursday during a speech in Sarasota, Florida.

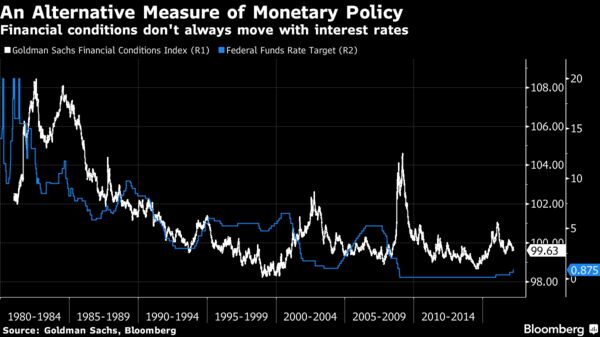

The speech, titled “The Importance of Financial Conditions in the Conduct of Monetary Policy,” echoed remarks he made 21 years ago, while also helping to explain why the Fed found it so hard to raise rates in 2016 and why many believe this year is looking better for them.

In the early 1990s, central bankers in Ottawa had a communications problem on their hands: Sometimes-volatile capital flows in international financial markets were leading to swings in the Canadian dollar. Those were obstructing the economic goals they were trying to achieve via their traditional policy tool, the short-term interest rate, according to Charles Freedman, deputy governor of the Bank of Canada from 1988 to 2003.

“To get that point across, we developed a ‘monetary conditions index’ which basically put the two channels together,” said Freedman, who is now an economics professor at Carleton University in Ottawa.

“Someone could look at that measure and say, interest rates haven’t moved but the exchange rate did move, and therefore market and monetary conditions have eased -- or tightened depending on which direction we’re going,” he said.

The idea caught on fast on Wall Street, including at Goldman Sachs, where Dudley was chief economist. In an October 1996 speech at Princeton University, he argued that “Fed officials should evaluate carefully the implications of changes in financial asset prices on the performance of the real economy,” according to a summary of his remarks.

Dudley cited a suite of monetary conditions indexes developed by Goldman economists which he said owed “a big debt to the path-breaking work of the Bank of Canada, in general, and Chuck Freedman, in particular.”

In February 1998, Dudley and his team at Goldman took a cue from then-Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, who had just testified before Congress that although inflation-adjusted interest rates had risen, “in virtually all other respects financial markets remained quite accommodative and, indeed, judging by the rise in equity prices, were providing additional impetus to domestic spending.” Two years later, the dot.com technology bubble burst.

Popular Tool

After the Greenspan testimony, Dudley’s team added a stock-market measure to their monetary conditions index, transforming it into a “financial conditions index” -- an increasingly popular tool with Fed watchers over the past two years as the Fed has sought to escape near-zero rates in a fragile global economy prone to bouts of market nerves.

Investors had already established the view that Greenspan would effectively provide a "put" to underpin the stock market by cutting rates when equity prices crashed, as he’d done in 1987. What made the financial-conditions approach different was the signal it sent to adjust policy in the other direction when asset prices rallied.

Today, Dudley’s position as vice chairman of the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee makes him an influential policy maker. That sway, and his long-standing focus on the importance of the stock market, means Chair Janet Yellen’s Fed may be more sensitive to outsize stock-price swings in both directions than previous committees.

In 2016, that focus translated into only one rate increase -- even though Fed officials projected four at the beginning of the year -- as a surge in borrowing costs that hit businesses kept policy makers sidelined until December.

Tightening Phase

This year, the story is changing. The FOMC has already hiked once and is aiming for two more, a prospect investors assign better-than-even odds.

“What is different this year versus previous years is sentiment is much improved, and that sentiment has translated into easier financial conditions, not necessarily more buoyant actual data,” Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays in New York, said.

“Easier financial conditions ultimately made it easier for them to go in March -- they had been thrown off their plans in previous years in part because sentiment wasn’t strong and financial conditions tightened,” said Gapen, who worked at the Fed Board in Washington during the financial crisis.

In a press conference following the FOMC’s March 15 rate hike, Yellen told reporters “the higher level of stock prices is one factor that looks like it’s likely to somewhat boost consumption spending,” citing “some of the more prominent analysts and indices” that have showed despite recent rate increases, overall financial conditions are actually easing.

Opposing Forces

One of those prominent analysts is Jan Hatzius, who worked for Dudley at Goldman and succeeded him as the firm’s chief economist. He helped Dudley refine the financial conditions index over the years and believes if it continues to indicate that conditions are easing despite the FOMC’s best efforts to tighten, officials may even decide to speed up the pace of increases to offset that effect.

“The concern is that financial conditions are quite easy and we are generating a sizable positive impulse to growth at a time when the economy seems to be at full employment and inflation is close to the Fed’s target,” Hatzius said. “So, at a time when you really probably want more trend growth rather than well-above-trend growth, it seems like we are on track for a period of well-above-trend growth.”

Some FOMC participants, like Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren, are already making that case. He said in a March 29 Bloomberg Television interview that “we don’t want to grow so much faster than potential at this point,” as he argued for four rate increases in 2017.

Ultimately, the Fed’s response to easier financial conditions should hinge on whether or not that boost in business sentiment translates to an actual acceleration in consumption, said Freedman.

“Stock markets go up. That in itself is not relevant,” he said. “What is relevant is its effect on people’s willingness to spend.”